Status and Treands

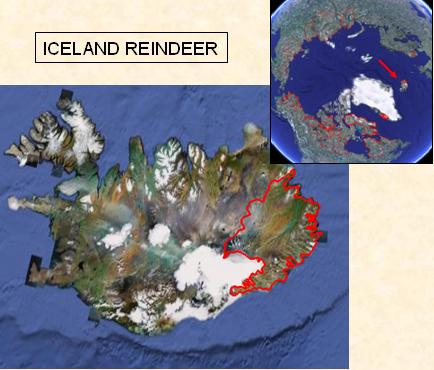

Reindeer were introduced from Norway to four different areas in Iceland in the late 18th century but three of the herds had disappeared or died out before 1930. The Norwegian animals were of semi-domesticated origin but have always been feral in Iceland. The present day population is confined to East Iceland.

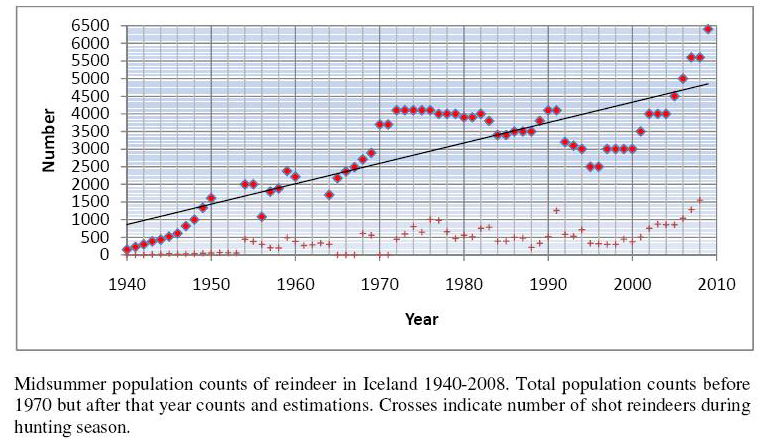

The reindeer population increased in size throughout the early 19th century, although actual population size at the time is unknown. The population declined again in the latter half of that century because of hard winters and overgrazing and is believed to have consisted of only a few hundred individuals in 1939. By then the herd was mostly confined to the northeast highlands in the precipitation shadow of the Vatnajökull Ice cap. After this the population gradually increased in size, spending summers close to Vatnajökull glacier and migrating east and north in autumn and descending to lower ground in winter.

Censuses were made in midsummer on horseback 1940-1953 and from an aeroplane after 1954. Around 1970 the herd had split up to about six subpopulations. Around half of the population spent the entire year in the eastern fjords and in the adjoining mountains and the rest on the highland plateau north of Vatnajökull glacier. The population is increasing although 20-25% of the total summer population is hunted annually. The estimated winter population in 2008-2009 is 5200 animals and expected to be around 6500 in autumn 2009.

Management

Before starting a discussion on population management of the Icelandic reindeer it might be good present certain historical and ecological points. Large natural herbivores didn´t exist in Iceland before the reindeer was introduced over 200 years ago and the vegetation is vulnerable to grazing. Secondly the reindeer live in an area that was, and still is, utilized by farmers as pastures for sheep and other livestock and for wood plantations in the lowlands.

When it became clear that the reindeer were here to stay and were thriving and multiplying, a management plan was needed to hinder deterioration of highland pastures and encroachment of cultivated land.

The management plans have changed and evolved with time. What started as an uncontrolled harvest with primitive means, by a few keen and sturdy farmers 200 years ago, has become a highly desired and strictly managed hunt.

The range of the reindeer is separated into nine hunting areas and the annual quota is divided between these areas to disperse hunting pressure and prevent too high density in any region. Quota is given out yearly based on annual information about density, population size, composition of age and sex and other information. Condition of pastures or complaints about encroachment on cultivated farmland is also considered. Quota suggestions are put forth annually by East Iceland Natural History Institute to the Reindeer Committee and sent from there to the Ministry of Environment where the final decision is made.

The hunting season is from 15 July until 15 September. Between 15 July and 1 August hunting is restricted to adult bulls outside the main cow-calf areas. Hunters are encouraged to harvest calves that belong to culled females; other calves are protected and so are male yearlings.

The Wildlife Management Department of The Environment Agency of Iceland is in charge of hunting in Iceland and regarding reindeer hunting it works in close collaboration with East Iceland Natural History Institute. Most of the income from the hunting is shared amongst landowners.

Every hunter has to hire a specialized reindeer guide who makes sure that the hunt is performed safely and correctly. The assistance of experienced guides helps to fill the set quota and thus all management is made more effective and exact. The reindeer guides record certain information about the killed animal and may gather samples for research purposes if required.

Threats

The Icelandic population today derives from 35 animals that were set ashore in the north east of Iceland in 1787. Possibly another 35 animals set a shore in Eyjafjörður in the north, integrated later into this founder population. A comparison study between the Icelandic reindeer population and semi-domesticated reindeers from Norway suggested that founder effects were highly active in determining the genetic structure of the population (Røed et al. 1985). The results further implied that the genetically effective founder population was possibly less than 15 animals.

So far, the effect of this genetic bottleneck has not influenced the body condition or fertility of the population noticeably. In general natural mortality is low, and fertility and calve survival are high.

Because of its isolation Iceland lacks many of the normal threats that haunt continental species. The island has no large predators and insects, parasites and diseases are few and not of consequence to the population so far. These protected surroundings together with low genetic variability in the Icelandic reindeer population, makes them especially vulnerable to possible future ecological changes.

Harsh winters with widespread non-penetrable ice crust and lack of available food source have so far been the main reason for high mortality in singular years. Severe winters were common in the last half of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th. In this period the population declined rapidly and disappeared from large areas. Probably only a few hundred animals survived and the population may have gone through another genetic bottleneck.

Possible climate changes with consequential changes in vegetation and food availability might affect the population in future. In the last ten years or so the winters have been mild with above average winter temperatures and little snow. So far these climate changes seem to increase winter and early calf survival. In the long run mild winters can mean more ice with possible non-penetrable ice cover and less snow. Less snow might again mean more exposed overgrowth and faster withering of vegetation during summer because of dryer soil.

Human caused disturbances and land use activities such as roads and industrial projects have already fragmented the reindeer habitat somewhat with potential cumulative effects that have yet to be revealed. National parks and better roads have lead to increased access and more traffic which again will lead to increased disturbance. Numbers of animals that are killed in the traffic have increased noticeably and might continue to rise in future. Little is known of how sensitive the Icelandic reindeers are to human disturbance. Originating from semi-domesticated animals and living for more than 200 years in predator free surroundings might make them more relaxed to human caused disturbance. On the other hand heavy annual hunting pressure is likely to keep them on their "toes" around human settlement and sensitive to stress cause by human activities.

Reports

Aschfalk, A., Skarphédinn G. Thórisson 2004. Seroprevalence of Salmonella spp. In wild reindeer (Rangifer tarandus tarandus) in Iceland. Veterinary research communication 28 (3):191-195.

Chase L.A., Eugene H. Studier and Skarphedinn Thorisson 1994. Aspects of nitrogen and Mineral nutrition in Icelandic reindeer, Rangifer tarandus. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 109A, 63-73.

Egilsson, K. 1983. The food and pastures for reindeer in Iceland. Orkustofnun OS-83074/VOD-07. In Icelandic with English summary.

Gaare, E. og Eigil Reimers 1978. Tillaga um rannsóknir á hreindýrum og beitarlandi þeirra á Íslandi (Proposal for a study of Reindeer and ranges in Island.). In: Thórisson, S. 1983. The history of reindeer in Iceland and reindeer study 1979-1981. Orkustofnun OS-83072/VOD-06. In Icelandic with English summary.

Gudmundsdottir, B 2006. Parasites of reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) in Iceland. MSc thesis. In Icelandic with English summary.

Gudmundsdottir, B, K. Skirnisson 2005. Description of a new Eimeriaspecies and redescription of Eimeria mayeri (Protozoa: Eimeriidaea) from wild reindeer Rangifer tarandus in Iceland. J. Parasitol., 91(2):353-357.

Gudmundsdottir, B, K. Skirnisson 2006. The third nemly discovered Eimeriaspecies (Protozoa: Eimeriidae) described from wild reindeer, Rangifer tarandus, in Iceland. Parasitol Res. DOI 10.1007/s00436-006-0210-3. Springer

Nellemann, C., Vistnes, I., Thórisson, S. 1999. Environmental impacts of the Fljótsdalur and Kárahnúkjar hydroelectric power supply to an aluminum smelter by Norsk Hydro in Iceland. Preliminary assessment of impacts on reindeer. NLN og NINA.

Hersteinsson, P 1991. Hreindýraveiðin árið 1990. (The reindeer hunting in 1990). Fréttabréf veiðistjóra (Wildl. Management News) 7: 26-29. In Icelandic with English summary.

Hersteinsson, P 1991. Er íslenski hreindýrastofninn of stór?. (Is the Icelandic reindeer population too big?). Fréttabréf veiðistjóra (Wildl. Management News) 7: 33-41. In Icelandic with English summary.

Hersteinsson, P 1992. Hreindýraveiðin 1991. (The reindeer hunt in 1991). Fréttabréf veiðistjóra (Wildl. Management News) 8: 28-32. In Icelandic with English summary.

Hersteinsson, P 1992. Nýjar reglur um stjórn hreindýraveiða. (New regulation on reindeer hunting). Fréttabréf veiðistjóra (Wildl. Management News) 8: 36-38. In Icelandic with English summary.

Pálsson, S.E., K. Egilsson, S. Þórisson, S. M. Magnússon, E. D. Ólafsdóttir & K. Indriðason 1994. Transfer of Radiocaesium from Soil and Plants to Reindeer in Iceland. J. Environ. Radioactivity 24(1994): 107-125.

Røed, K. H., Soldal, A. V. and Thórisson, S. 1985. Transferrin variability and founder effect in Iceland reindeer, Rangifer tarandus L. - Hereditas 103: 161-164. Lund, Sweden.

Thórisson, S. 1980. Status of Rangifer in Iceland. In (Reimers, E., Gaare, E. and Skjenneberg, S. (eds.): Proc. 2nd Int. Reindeer/Caribou Symp., Rörös, Norway, 1979. Direktoratet for vilt og ferskvannsfisk, Trondheim.

Thórisson, S. 1983. The history of reindeer in Iceland and reindeer study 1979-1981. Orkustofnun OS-83072/VOD-06. In Icelandic with English summary.

Thórisson, S. 1984. The history of reindeer in Iceland and reindeer study 1979-1981. Rangifer 4 (2): 22-38.

Þórisson, S. 1991. Hreindýratalning dagana 15.-21. apríl 1991. (Total population count of reindeer in Iceland in April 1991). Fréttabréf veiðistjóra (Wildl. Management News) 7: 30-32. In Icelandic with English summary.

Þórisson, S. og Páll Hersteinsson 1992. Hreindýratalning í apríl 1992. (Total population count of reindeer in Iceland in April 1992). Fréttabréf veiðistjóra (Wildl. Management News) 8: 33-35. In Icelandic with English summary.

Williams T.H. & Heard D.C. 1986. World status of wild Rangifer tarandus populations. Rangifer, Special Issue 1, bls. 19-28.

Þórhallsdóttir, A.G. 1981. Beitvalg hos sau og rein på Vesturöræfi Island. Hovedoppgave ved Norges landbrukshøgskole, Institut for Naturforvalting (handrit), 107 bls.

Contacts

Skarphéðinn G. Þórisson (Skarphedinn G. Thorisson)

Náttúrustofa Austurlands (East Iceland Natural History Institute)

Midvangi 2

700 Egilsstadir

Iceland

tlf: (354) 4712813 Mobile: (354) 8626774

E-mail: skarphedinn 'at' na.is

www.na.is

Rán Þórarinsdóttir (Ran Thorarinsdottir)

Náttúrustofa Austurlands (East Iceland Natural History Institute)

Tjarnarbraut 39a

700 Egilsstadir

Iceland

tlf: (354) 4712774 Mobile: (354) 8665756

E-mail: ran 'at' na.is

www.na.is